I was scrolling through Youtube comments under a video by Anthropic where someone wrote: “you say wow way too much” And I froze. Because I knew, I do that. If you have seen or listened to any of my podcasts, you will know that I’m the guy saying “wow” or “that’s amazing,” asking follow-up questions, leaning in a little too much. Trying to show I care. Trying to bond.

At Navy boot camp, back in 1993, there were eighty of us in the end-of-training company photo, looking smart in our dress blues. Only one smiling face… mine. I caught hell for that. But I couldn’t help it. That smile was real. I was proud to be there. That’s always been my instinct: be open, connect, be enthusiastic, stay curious.

Some of that started early. My brother, Mark, died when I was eleven. He was fourteen and had been diagnosed 18 months earlier with an aggressive brain tumor. I went from younger sibling to only child overnight, but my mother (my parents were divorced) did the best she could. But something cracked open in me, a void appeared, a deep ache to be part of something bigger, to not feel so alone, even if it meant carrying more than I should.

Having watched Top Gun and Navy Seals many times over (again, I was young and naive at the time, seeking excitement and new levels of greater), the Navy felt like the right answer in 1993. Nine years of chasing that feeling of brotherhood. There was good work and hard work. Humanitarian missions, drug interdictions, long deployments under the NATO flag. But the stuff that sticks isn’t in the mission logs or commendations. It’s the sound of someone’s voice breaking after hearing their kid was rushed to the hospital thousands of miles away, with no way home. It’s the suicide attempts. The ones we stopped. The ones we didn’t. The ones where someone just couldn’t take it anymore.

These things bonded us, sure, but the connection always felt temporary. Contingent on crisis. If things were calm, we drifted. And when I left the service, two Captain’s masts later, that drift felt permanent.

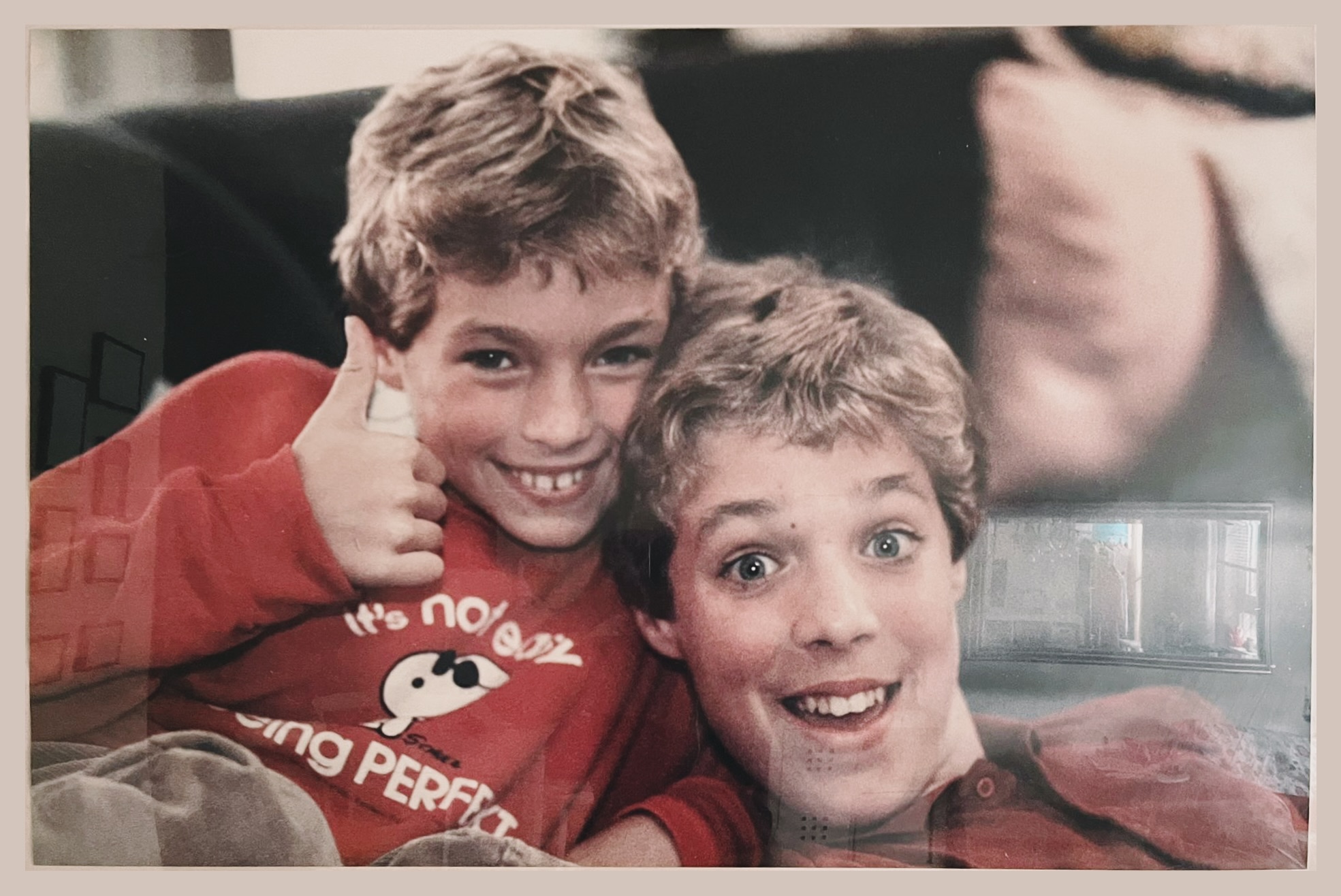

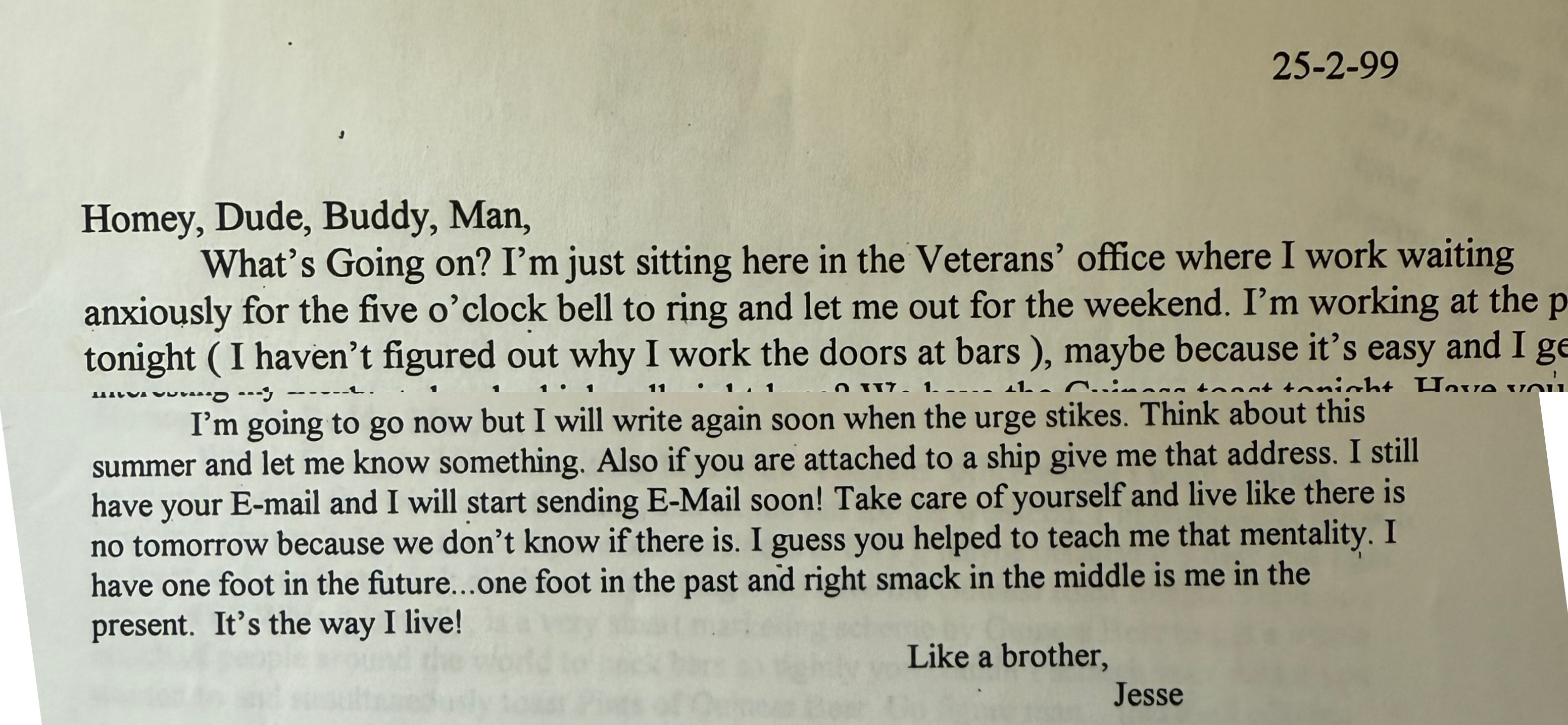

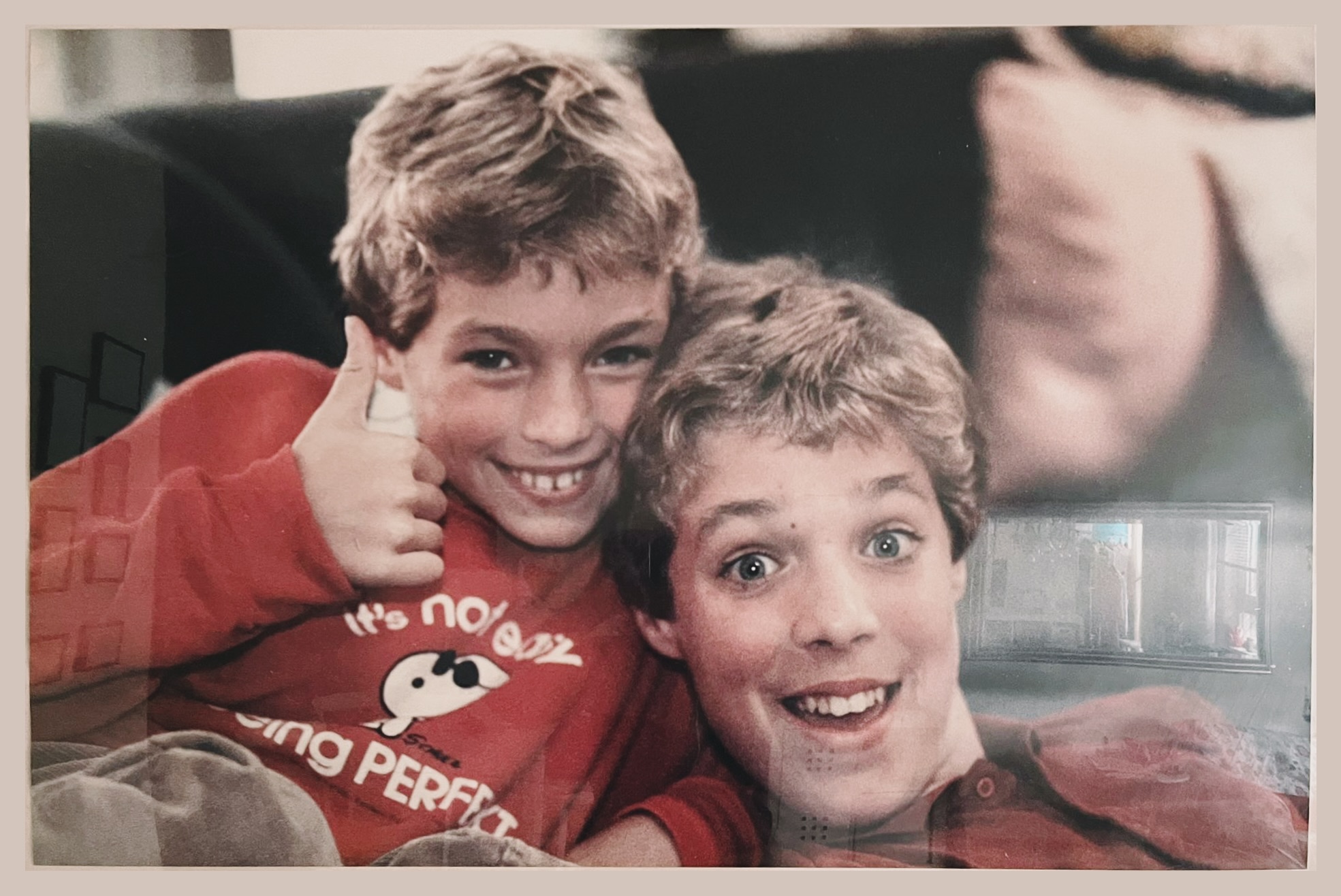

Jesse was the exception. He was my buddy, my brother in arms. A friend who saw the whole mess and still showed up, and more importantly, introduced me to the Beastie Boys. Then, not long after I left the Navy, Jesse died, under circumstances too close to how I lost my brother. It hollowed me out, again. I got to say farewell to him at his home in South Carolina a month before he passed, but the PTSD I’d been ignoring came roaring back. I drank more. Got into debt more, to feed that retail therapy beast. I disappeared into places I didn’t remember arriving, literally, and figuratively. What used to be dark comedy among veterans became something else entirely. A slow-motion unraveling.

And the cruelest part? I wanted love, connection, belonging… but pushed it all away the second it got close. Depression will do that. It teaches you to flinch before you’re even touched. To say goodbye before anyone asks you to stay. Something I still catch myself doing to this day.

Then I met someone who saw all of that and didn’t run. My wife didn’t try to fix me. She just made therapy non-negotiable. Not as an ultimatum, but as a condition of building something real. And she was right. And we did.

There was a turning point during one EMDR session where I recalled the image of my brother setting the table, crawling over the floor from the kitchen to the dining table, with the cutlery in his bathrobe pocket, while being paralyzed on one side. The pain of not helping him, being lazy, and taking it for granted, the drive and will within him. The feeling that I could never match up to that. It should have been me. I felt the weight I’d carried since eleven, this grief-disguised-as-drive, finally shift a little. Not vanish. But loosen its grip on me.

Still, I needed something. Some community. A way to connect that wouldn’t put me at risk of getting hurt again.

Interestingly, I discovered it in digital analytics around 2005, shortly after I met my wife.

There’s something about this corner of the industry, whether it's martech, data, analytics, or whatever, that felt human in ways I hadn’t expected. People didn’t pretend to have it all figured out. They admitted mistakes. For many it was and remains a case of learn and move on. They taught without condescension. They asked questions that felt honest, not performative.

That generosity gave me room to breathe. It reminded me that maybe not all connection has to be temporary. And that changed something.

But I still keep some distance. That’s why I freelance now after having tried agency and client-side jobs for 10 years. The freedom of contracting keeps me in balance. It lets me be there for my family, with our eldest son who around 10 years ago was diagnosed with a benign brain tumor, the sick irony of life, but I was more resilient this time around.

Contracting allows me to be fully present at work, yet still hold back just enough. I can contribute, connect, and help build something, but I don’t have to stay. I don’t have to belong fully. That sounds sad, but it’s safer. I’ve had contracts where it genuinely hurt to say goodbye, and that pain reminded me why I draw lines the way I do. That’s what I keep convincing myself of, though. The jury is still out on that one.

At nearly 50, I’m the sum total of everything I’ve seen. But it’s not just a sum, it’s addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Some experiences added to me. Some took pieces away. Some split me open. Others multiplied the meaning of things I thought I understood. All of it shaped me.

Which brings me to my son, our youngest.

He’s what the school system politely calls “gifted,” though he doesn’t fit the model. He learns fast, obsesses over things, and melts down when he hits walls. He doesn’t slot neatly into social groups. Just does his own thing, tries to be himself. Which, again, sounds familiar.

He got deep into manga and asked me to take him to ComicCon. I’m a lifelong sci-fi fan. Fallout, The Expanse, Star Wars’ Andor, so I was game. But I had assumptions about cosplay and the people who do it. I thought it took wild courage to wear that kind of outfit in public.

Turns out, I had it backwards.

ComicCon wasn’t about extraordinary bravery. It was about ordinary acceptance. People weren’t trying to stand out, they were finally able to just be themselves. The costumes weren’t rebellion. They were belonging.

And my son? He thrived. Talked to strangers like it was the most natural thing in the world. Got respect from the jump. Found his people. For once, he wasn’t the weird kid. He was just a fan among fans.

Watching him, I realized I knew this feeling. I’d found it in our professional community. The one we build in chat threads, conference calls, and post-conference hotel bars. The one where you can say, “I’m not sure,” and no one punishes you for it. Where vulnerability isn’t a weakness, it’s credibility.

ComicCon and our little corner of martech, digital analytics, and our common love for data share something rare: they assume you belong until you prove otherwise. Not the other way around.

For years, I thought belonging meant finding people who were just like me. Same experiences, same wiring. The Navy gave me that for a while, but only under pressure. What I’ve learned since is that real belonging isn’t about sameness. It’s about shared values. At ComicCon, that’s enthusiasm. In our world, it’s curiosity.

The people who show up damaged but still willing to try? They’re the ones others gravitate toward. Not because they’ve got all the answers, but because they don’t pretend to.

So yeah. This is me.

Someone who lost too much too young. Who made mistakes, repeatedly, and tried to hide. Who spent years chasing a connection while also running from it at the same time. Who found a strange kind of home in professional communities that value honesty more than polish. Someone still learning how to stay in the room when things get quiet. Someone who says, and will continue to genuinely say, ‘wow’ often.

My son showed me what it looks like to walk into a space and just assume you belong. No armor. No apology.

That’s what I’m working on. Being human, being me.

Who are you?

Connect with me on LinkedIn:

Follow Martech Therapy on:

Discussion