Every vendor promises the same thing “you only pay for what you use”.

It’s a comforting line, one that suggests control and fairness. But in Martech, especially when you look at Customer Data Platforms (CDPs) and Customer Engagement Platforms (CEPs), the definition of use changes depending on who you ask.

Most CDPs still price around data management, how many profiles you store, how many events you collect, or how many systems you connect. It’s a model born from infrastructure.

Meanwhile, CEPs are leading the move toward usage-based pricing, a model built on engagement itself. Platforms like Braze and Zepic now let clients pay for communication moments rather than for stored data. Every push, email, or in-app message becomes a measurable transaction. Others, like mParticle, experiment with hybrid credit systems that let you flex your budget across modules such as ingestion, activation, or AI.

At first glance, this feels more transparent. You pay for value in motion, not data at rest. But the more you study these models, the clearer it becomes, but transparency doesn’t mean simplicity.

The geometry of pricing

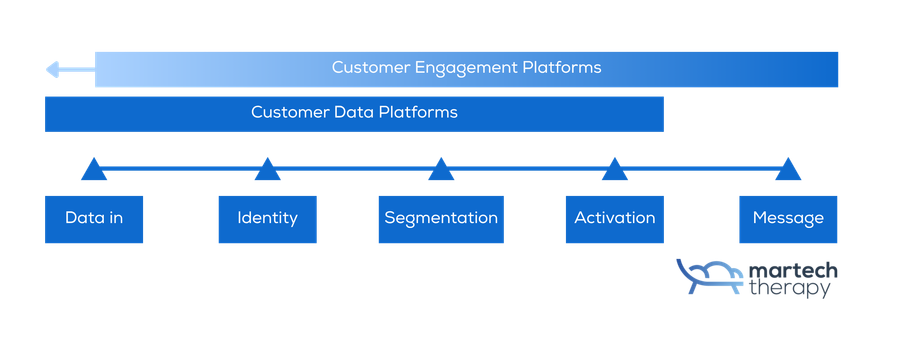

Pricing in Martech mirrors how each vendor understands value.

- CDPs live close to the data layer, so cost scales with storage, volume, and transformation.

- CEPs live close to the customer layer, so cost scales with engagement frequency.

That difference sounds obvious, yet it’s the source of endless confusion. Both camps talk about usage, but one means data usage and the other means communication usage.

A CDP might call 10 million tracked events “usage”. A CEP might call 10 million sent messages the same thing. On paper the units look identical. In reality they describe two very different types of activity: one analytical, one experiential.

Decoding what “usage” really means

Traditional CDPs meter value in data terms:

| Metric | What it represents |

|---|---|

| Profiles / Records | How many individuals, known and anonymous, sit in your system |

| MTUs / MAUs | Profiles that generated or received data within a billing period |

| Events | The behavioral exhaust from your apps and sites |

| Connections / Destinations | The number of data pipelines you maintain |

| Modules | Extras like AI scoring, consent, or identity graphs |

CEPs, on the other hand, meter value in engagement terms:

| Metric | What it represents |

|---|---|

| Messages or communication moments | Pushes, emails, in-app cards, content updates |

| Data points | Write actions that update customer attributes |

| Credit pools | Flexible budgets you can allocate toward the features that matter most |

This is the real divide. CDPs charge for the data you hold; CEPs charge for the actions you take.

When fairness gets complicated

Usage-based pricing sounds democratic, pay only for what you use. But what you use depends entirely on your business model.

A travel company that tracks millions of micro-events per booking will experience event-based pricing very differently from a subscription service with a small, loyal customer base. Likewise, a brand campaigning with daily push notifications will see a very different usage curve from one that only emails monthly newsletters.

That’s why two organizations on the same platform can see wildly different bills.

Braze, for example, now offers some customers the option to move from its older data-point model to a true usagemodel. It’s flexible, and for some, fairer, but several renewal stories suggest it can be more expensive for brands with high automation or frequent communication cycles.

Event-based CDP pricing can show the same bias in reverse. It can be great for efficient tracking setups, but punishing for those with exploratory teams that instrument every action.

In both worlds, the model quietly rewards some business patterns and penalizes others. That’s why it’s crucial to map your pricing sensitivity to your actual communication reality before signing anything.

Because pricing isn’t only a vendor tactic, it’s a mirror of how your organization operates.

When overages write the future

Every SaaS contract includes a “fair-use” or “burst” clause. It sounds friendly, a little cushion for growth, or initial loading of data, but that line item often defines your renewal.

A few extra million events, a coding error (yes, been there and done that), or a seasonal send spike can push you over your contracted threshold within weeks. Vendors will true-up the difference at renewal and quietly adjust your baseline upward. What started as a one-off success becomes a permanent price floor.

For CDPs, overages usually come from data spikes, new tracking, campaign tagging, or product instrumentation. For CEPs, they stem from engagement surges like a new messaging journey, a big sale, or a re-activation campaign.

The smartest teams negotiate growth buffers upfront. With that I mean predefined headroom for natural expansion that doesn’t trigger immediate penalties. Even five to ten percent can make a difference when the next product launch hits.

Why comparisons break down

Comparing CDP and CEP pricing is like comparing the price of storage with the price of electricity. One keeps your data safe while the other powers what you do with it.

Even within the same category, language varies. Some CDPs count every anonymous profile when others only known ones. One measures events ingested and another events processed. Some CEPs bill by contact, others by message, and some by both.

Then come hybrids like Bloomreach Engagement, which combines a module-based subscription with expected usage levels per channel. You pay for the capability plus a forecasted volume, not for every profile or every send.

So when you stack up quotes, you’re not comparing like-for-like, you’re comparing worldviews.

Reading a quote like a strategist

When you receive a proposal, read it backwards. Find the metric that actually drives the total cost. If it’s events, map where they come from. If it’s profiles, clarify what counts as active. If it’s usage, model your typical campaign cadence, including your peaks, not your averages.

| Meter type | What it means | Hidden risk | What to clarify |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profiles / Records | The total number of customer identities stored in your CDP | Duplicate profiles or inactive users can inflate your bill | Define “active” and confirm if anonymous profiles are counted |

| Events | Every tracked behavior (click, purchase, view) captured from apps or sites | Event spikes from testing or analytics tags can trigger overages | Clarify if pricing is for events ingested or processed |

| MTUs / MAUs | Monthly Tracked or Active Users who generated data or were targeted | Definitions vary widely; some vendors count all data changes | Ask for written definitions and examples in your contract |

| Messages / Communication moments | Pushes, emails, or in-app deliveries that reach users | Frequent automation or retries can multiply billable sends | Confirm if retries, previews, or API tests count as messages |

| Data points | Profile write actions or updates in engagement platforms | Rapid attribute updates can consume quota quickly | Clarify if updates batch together or count individually |

| Credit pools / Usage budgets | Flexible credit systems you can spend across modules | Burn rate is hard to predict; costs can move between teams | Ask how credits are measured, reset, and repriced at renewal |

This exercise isn’t about catching vendors out, not in the least. It’s about understanding the rules of their economy. Once you know what moves the number, you can align your internal habits to it or negotiate the definition itself.

It’s astonishing how often definitions change mid-contract. A “tracked event” might later become a “processed event.” A “message” might expand to include in-app impressions. Having those terms locked in writing is worth more than a small discount.

When price stops being the point

The easiest mistake in Martech is to treat cost as the enemy. Price only matters relative to outcome. If a platform helps you run smarter campaigns, shorten lead time, or reduce manual data work, the higher invoice might still represent a better deal.

Pricing, in the end, is a language for describing value movement. The question is whether that movement aligns with your goals.

If your CDP contract measures data quality and accessibility, invest in keeping your data clean and valuable. If your CEP contract measures communication moments, invest in relevance and efficiency so every message earns its cost.

The goal isn’t to game the model but to understand what it rewards and to make that reward system work for you.

Before I go, let me leave you with this

There’s no universal “right” pricing model. Event-based, profile-based, usage-based, each has its own truth, and each exposes a different aspect of how you operate.

So, before you negotiate your next renewal, step back and ask:

- What does our current pricing model say about how we work?

- Does it still fit the way we communicate with customers?

- And if the platform truly helps us grow, at what point does the conversation shift from cost to value?

Pricing tells only half the story. Even when you understand every meter and definition, the real costs often start after the contract is signed, in the teams, tools, and cloud cycles that keep your data flowing. That’s where we’ll go next, in Part 2: The Hidden Costs of Composability, an inside look at why “paying less for software” can still mean spending more to make it work.

Discussion