Last week, in the first part of this series, I shared some experiences on how to read Martech pricing. In this second part, I want to examine the other end of the product spectrum and learn to live with it. Once you understand how vendors define usage, value, and fairness, a new question appears:

What happens when you try to escape those models altogether?

That’s where composability enters the story. It promises freedom from rigid licenses, bundled modules, and predefined ways of working. Build your own stack, plug in best-of-breed tools, let each component scale on its own terms. On paper, it feels like the antidote to everything Part 1 revealed.

But... freedom has an operational cost. When you stop paying vendors to manage complexity for you, that complexity doesn’t disappear, it moves in-house. The subscription line goes down, but another line rises in its place, such as engineering time, maintenance, monitoring, cloud usage, and orchestration overhead.

So while part 1 examined what pricing says, this article looks at what pricing skips. Because the real bill for a composable stack is rarely the one you sign. It’s the one you inherit.

The promise of composability

Composable Martech didn’t start as a financial movement. It began as a cultural one. Engineers wanted cleaner architectures, product teams wanted flexibility, and marketers wanted to stop waiting in ticket queues. Self-serve galore.

The MACH Alliance turned those ideas into a manifesto:

- Modular

- API-first

- Cloud-native

- Headless.

Each acronym spoke the same language of freedom.

And to be fair, composability does deliver on many of its promises. It encourages experimentation, speeds up iteration, and lets companies swap tools as they grow. For organizations with strong internal capabilities, it’s the first model that truly scales with ambition.

The trouble starts when ambition outruns capacity. Flexibility feels free... until you have to operate it. The more control you take on, the more invisible work you inherit with tasks like monitoring integrations, managing schema drift, tracking costs across APIs, and cloud workloads.

That’s where composability shifts from a technical decision to a financial one, and why understanding its hidden costs has become as important as understanding your stack’s design.

Simo: “Flexibility doesn’t remove complexity, it only shifts where the complexity lives. You don’t get rid of the operational burden, you just bring it closer to your own teams.”

Where the money actually moves

Composable stacks rarely collapse due to technology problems. They often collapse under the weight of maintenance. Each added service, connection, or pipeline introduces a small piece of overhead, none of which is significant on its own, but together they form a permanent layer of operational tax.

When companies calculate the savings from dropping enterprise suites, they often forget what replaces them: people & processes.

|

Cost type |

How it appears |

What’s often missed |

|---|---|---|

|

Human cost |

Data engineers, analytics engineers, DevOps, QA, FinOps, and solution architects |

Ongoing skill premiums and turnover risk |

|

Architecture cost |

Cloud compute, storage, reverse-ETL runs, retries, observability |

Costs scale with experimentation and API volume |

|

Integration cost |

Maintenance, schema drift, version upgrades, monitoring |

Each connection becomes its own micro-project |

|

Governance cost |

Data quality checks, privacy audits, compliance |

Manual oversight grows with every new tool |

Composable systems shift the financial center of gravity from licenses to operations. Vendors stop billing you for packaged services, and instead, you start billing yourself for the time and cloud cycles required to keep everything synchronized.

The illusion of reuse

One of the core promises of composability is reusability, something that boils down to "build once, use everywhere".

But reusable components still require re-testing, schema validation, and API updates with each new integration. Every “plug and play” connection hides a recurring cost in QA and governance.

It saves code, not time.

Teams often discover this when onboarding new channels. What looks like an easy connection becomes another sprint’s worth of coordination between Martech, product, and data engineering.

A composable setup gives you creative freedom, but that creativity comes with the same accountability as code.

The human factor

In traditional Martech suites, you pay vendors for predictability. In composable setups, you pay your people for resilience.

That change sounds empowering, and it can be, but it comes with new dependencies. Think along the lines of specialized skill sets, role overlap, and the ongoing cost of coordination.

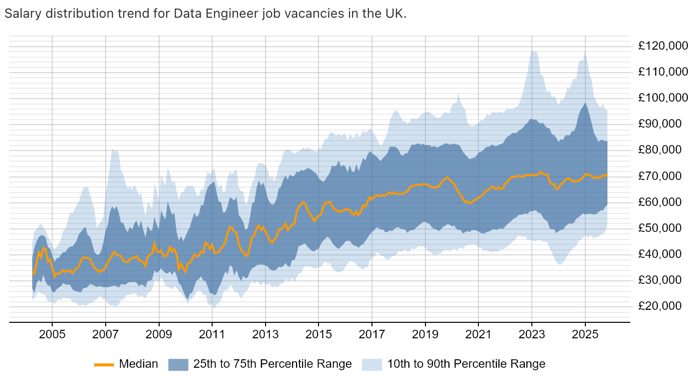

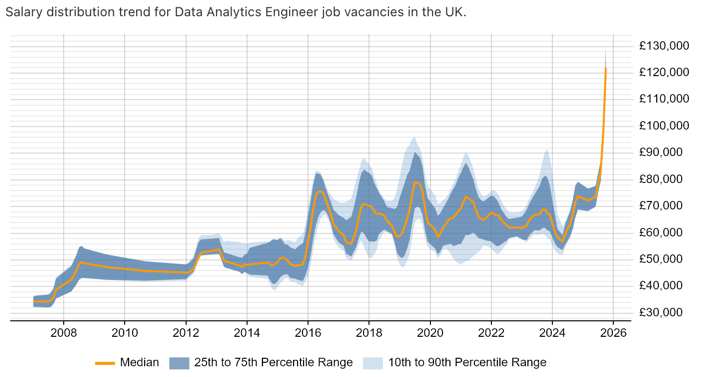

Composable teams need builders, not just operators. And builders are expensive. Salaries for experienced data engineers and analytics engineers have risen faster than SaaS inflation. Add in onboarding, knowledge transfer, and context switching between multiple tools, suddenly the “savings” from skipping a suite license disappear into payroll.

The architecture paradox

Composable stacks start out lean and elegant. Then they grow.

Each new tool promises better control or capability, but every addition adds coordination. Over time, that coordination becomes the architecture. What was meant to be a set of modular choices turns into an ecosystem that demands constant orchestration.

[Visual prompt: a stacked diagram showing “Data warehouse at center → Reverse ETL → Activation tools → Channels,” surrounded by monitoring and QA layers.]

When you map total cost of ownership (TCO) over three years, the pattern often reverses expectations. Year one looks cheaper. Year two breaks even. By year three, ongoing operations surpass the old suite license.

Control, but at what price?

Composable systems return control to the organization, but control is not free. Every new freedom, self-hosting, custom routing, in-house identity, creates a new responsibility.

You stop paying vendors to handle risk, and start paying internal teams to carry it.

That’s not a bad trade if you need sovereignty or unique orchestration. But it changes your risk profile. Vendors have SLAs and global redundancy, while internal teams have calendars and competing priorities.

Control, in this sense, is a cost category disguised as a benefit.

How to calculate composable TCO

There’s no single formula, but there are common blind spots.

Direct costs are easy, a sum of tool subscriptions and cloud usage. Indirect costs are harder. How do you put an accurate price on people, partners, downtime, and lost velocity? Then comes volatility, the rate at which these costs change with scale.

|

Cost category |

Suite approach |

Composable approach |

Risk factor |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Licensing |

Fixed multi-year contract |

Variable modular subscriptions |

Predictable vs. flexible |

|

People |

Fewer, vendor-trained operators |

More, engineering-heavy teams |

Skill scarcity |

|

Cloud |

Included in license |

Billed per run/query/storage |

Volatile at scale |

|

Support |

SLA-backed vendor |

Internal/partner-managed |

Response time |

|

Governance |

Vendor policy |

Internal compliance |

Audit burden |

Treat composable adoption less like a procurement decision and more like an engineering investment. The return is flexibility, but the maintenance is forever.

When composable makes sense

Composable isn’t a mistake. It’s just not a shortcut as it is often made out to be.

It works beautifully for teams with mature data infrastructure, in-house engineering talent, and the appetite to own their stack. It also fits organizations experimenting with AI-native workflows or real-time orchestration, where customization outweighs simplicity.

But for smaller teams, junior teams, or overstretched departments, composability can introduce more friction than freedom. The question isn’t “is composable better?” It’s “are we ready to operate like a software company?”.

Remember, freedom without capacity is chaos.

Some final thoughts

In Martech, every pricing model hides a workload. Suites sell convenience. Composable platforms sell control. Either way, you pay for someone to hold the complexity, the only question is who.

Part 1 explored what pricing says; Part 2 has looked at what it hides. In Part 3, we’ll explore the middle ground: how to negotiate across both worlds, and what leverage still works when vendors start pricing in definitions instead of discounts.

Discussion